Thursday, October 30, 2008

Partisan Rangers

Jefferson Davis approved an act to authorize commissioned officers to form bands of Partisan Rangers.

As these groups practiced “hit and run” guerilla warfare, one could envision the roving bands of Partisan Rangers as somewhat akin to the Privateers sanctioned by the British Throne to harass the Spanish Armada during the 16th Century.

Stealthy bands of Partisan Rangers began to pillage areas in which Union troops sought to obtain food and horses. Emboldened by their success, they looted supply depots delightedly distributing captured stores of Federal food and materials to thankful Confederate troops. Occasionally, Partisan Rangers harassed or directly engaged the Union troops. When the action grew too dangerous, the Partisan Rangers mysteriously disappeared into the countryside with the aide of sympathetic civilians. Thus, Partisan Rangers proved an asset to the Confederacy as they diverted the attention and manpower of Union troops from their primary goal of fighting Confederate troops.

John Hunt Morgan, an experienced Mexican War veteran who had organized the escape of the Lexington Rifles from Kentucky, seized the opportunity to regroup his men and organize them into a Partisan Ranger band. Morgan much preferred the freedom of leading his own missions to the stifling boredom of taking his orders from superiors.

“The raiders who joined John Hunt Morgan in Kentucky at the beginning of the war belonged to the aristocracy. They descended from planters who had originally settled Virginia and North Carolina and now had created a new nobility in the Bluegrass state. Four years before the war they became known as the Lexington Rifles. At the start of the war they were sworn into the Confederate army as the First Kentucky Cavalry.” [i]

Meanwhile, average soldiers of both North and South were painfully discovering that the reality of war was far from the excitement promised by propaganda campaigns and veteran’s tales. Soldier's life was far from the romantic adventure many young volunteers had expected. When they weren't marching along dusty roads, sloughing through ankle-deep mud, suffering in sweltering heat of summer, or freezing in the snow storms of winter, they endured the tedium of camp life: continuous drilling, digging ditches, cutting wood, building shelter, and eternally foraging for sufficient food.

“April 1862, Cumberland River

Where is all that romance in camp life that you read about in so many novels...But where, where, is the romance, the pleasure of war? You can put it all in your eye."

~ Stephen Keyes Fletcher, 33rd Indiana Volunteer Infantry[ii]

July 8, 1862

John Hunt Morgan launched his first raid into Kentucky leaving a wake of burnt railroad trestles, cut telegraph wires, and ruined Union supplies.

“Morgan’s men believed in something that they risked their lives for. It was a heritage of courage, dedication, perseverance, self-sacrifice, and love of country, as they saw it.”

~ Sam Flora, President of the Morgan’s Men Association

Tales of Morgan’s adherence to the code of chivalry and gallant conduct during the raids captured the imagination of the Southern citizenry. Morgan enhanced the myth himself in letters to his friends.

“I was amused at the Yankee ladies. Poor things, they were going down to Nashville to see their friends. They crowded round me crying: ‘Oh, Capt. Morgan what are you going to do with our trunks? What are you going to do with us?’ I give you my word Mrs. French – the trunks came first. They doubtless had in them some of those three story Yankee Bonnets to astonish Nashville with.

One pretty girl – she had been only lately married – her husband was with her – a Federal officer in poor health – this pretty girl grasped my hand in both her’s [sic] sobbing, ‘Oh, Capt. Morgan what will you do with my husband? I could not resist such a sweet face. I said, ‘Madame, I do not know whether I am doing you a kindness or not – but if you desire it – your husband shall accompany you home.’ She kissed my hand and thanked me a thousand times – my hand Mrs. French, that had not been washed for two days – and was as black as it could be besides with firing that train.” [iii]

Newspapers across the county carried tales of Morgan’s exploits. Notoriety pleased Morgan who envisioned himself as a Southern champion.

“When the Civil War broke, Morgan and his ‘terrible men’ were ready. Morgan was a regular officer, and took orders (when he felt like it) from his superiors, but the North persisted in regarding him as an irregular, capable of every atrocity from horse-stealing to killing the wounded. Biographer Swiggett says Morgan obeyed the rules of civilized warfare, but admits his men were fond of ambushing Federal pickets, of suddenly displaying a flag of truce to get themselves out of a tight corner. Braxton [Bragg] West Pointer, who was Morgan's nominal commander, disliked him, disapproved of his aims and methods. But Morgan's gallantry and success in raiding through Kentucky and Ohio soon made him a bogeyman to the North, a hero to the South. One of his tricks was to capture a telegraph station, send fake messages to foil the enemy. Once he wired to his disgruntled pursuer: "Good morning, Jerry! This telegraph is a great institution. You should destroy it as it keeps me too well posted.”[iv]

The heat of the summer was playing havoc with both armies. One of Morgan’s great assets was having men within the unit who personally knew the land, the waterways, and the location of hidden springs.

"During the summer of 1862, Kentucky was going through one of its worst droughts ever. Both armies were looking for water sources.”[v]

July 16, 1862

"Lexington and Frankfurt ... are garrisoned with Home Guard. The bridges between Cincinnati and Lexington have been destroyed. The whole country can be secured and 25,000 to 30,000 men with join you at once.”

~ John Hunt Morgan’s Telegraph Message to General Edmond Kirby Smith

John Hunt Morgan reported to General Edmond Kirby Smith that 25,000 to 30,000 Kentuckians were prepared to join the Confederate forces.[vi] This report appears to have been one of Morgan’s many exaggerations to his superiors. The Achilles’ heel of Morgan’s leadership was his own unrestrained personality. His egotism, over confidence, and shameless ambitions would lead the Kentucky Cavalry to disaster time and time again.

Disaster in battle was becoming well known throughout the Confederacy. Southern ministers began to refer to casualties and defeats as a requisite “Baptism in Blood.”

"All nations which come into existence at this late period of the world must be born amid the storm of revolution and must win their way to a place in history through the baptism of blood."

~ Episcopal Bishop Stephen Elliot

July 22, 1862

The Dix-Hill Cartel came into effect. The Union and Confederate governments reached agreement in regard to the exchange prisoners by modeling a plan after an earlier cartel arrangement used between the United States and Great Britain in the War of 1812. Their cartel agreement established a scale of equivalents to manage the exchange of military officers and enlisted personnel. For example, a naval captain or a colonel in the army would exchange for fifteen privates or common seamen, while personnel of equal ranks would transfer man for man.

Meanwhile, John Hunt Morgan campagianed his superiors for a full scale invasion of Kentucky, promising the support of the citizenry and thousands of eager volunteers.

“The feeling in Middle Tennessee and Kentucky is represented by Forrest and Morgan to have become intensely hostile to the enemy, and nothing is wanted but arms and support to bring the people into our ranks, for they have found that neutrality has afforded them no protection.”

~ General Bragg, August 1, 1862

August, 1862

John Hunt Morgan began a second raid into Kentucky.

“I, in my justifiable attacks on Federal troops and Federal property, have always respected private property and persons of union men. I do hereby declare that, to protect Southern citizens and their rights, I will henceforth put the law of retaliation into full force, and act upon it with vigor. For every dollar exacted from my fellow-citizens, I will have two from all men of known Union sentiments, and will make their persons and property responsible for its payment. God knows it was my earnest wish to have conducted this war according to the dictates of my heart, and consonant to those feelings which actuate every honorable mind, but forced by the vindictive and iniquitous proceedings of our Northern foes to follow their example in order to induce them to return to humane conduct, I will for the future imitate them in their exactions, retaliate upon them and theirs the cruelties and oppressions with which my friends are visited, and continue this course until our enemies consent to make war according to the law of nations.”

~John Hunt Morgan, The Vidette, August 19, 1862

August 14, 1862

Heeding Morgan, Confederate Generals Braxton Bragg and Edmund Kirby Smith invaded Kentucky.

“The extraordinary sight of 1,000 cavalrymen as they roared into tiny Scottsville, Kentucky was enough to convince young Isaac N. Hunt to join Morgan’s Raiders. After an impassioned speech by Gen. John Hunt Morgan at the Scottsville Hotel, Hunt joined up. Convinced of the sincerity of Morgan’s message that the men of Kentucky should join the Confederate cause, Hunt left his family home and rode off. As a private in Company C, 3rd Kentucky Cavalry, the teenager fought for more than one year until he was captured and sent to Camp Douglas.” [vii]

“Bragg was a poor choice [to command the Army of Tennessee], said critics of [Jefferson] Davis. Davis sent him to the Army of Tennessee because he was an old friend, and the President had faith in his abilities. He was no commander, even though he seems to have been a good organizer. But Bragg, to Davis’ way of thinking, was the best man he had for the Tennessee assignment.”[viii]

August 16, 1862

Kentucky Governor Beriah Magoffin resigned from office and was replaced by James F. Robinson. Robinson served out the remainder of Magoffin's term of office.

Kentucky swarmed with invading soldiers.

“Then there were days when a cluster of tents was pitched in a nearby field, and everyone moved heaven and earth to take these gray clad men all the food and clothing that could possibly be spared from our own scanty store, for these were ‘our boys’; our own ‘Johnny Rebs,’ and we'd all gladly go hungry and cold to aid them. We were ready to live and die for Dixie.”

~ Ella Johnson[ix]

“They are having a stampede in Kentucky. Please look into it.”

~ Telegraph from President Abraham Lincoln to Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck

August 29 - 30, 1862

The Battle of Richmond, Kentucky was fought in three phases. Union forces under General William B. Nelson suffered a disastrous defeat at the hands of Confederate General Edmond Kirby Smith and were forced to retreat in chaos and disarray. Approximately 4,000 of the retreating men were taken prisoner.[x]

“Of the 6,500 Union troops who went into battle, some 4,300 were taken prisoner and more than 1,000 were either killed or wounded. The Confederates, who were some 6,600 strong, lost only 128 men -- 118 who were killed and 10 listed as missing in action.

The battle was fought in three phases -- at Kingston, Duncannon Lane and in the Richmond Cemetery -- during a time when Madison County was in the throes of a severe drought. The temperature was some 96-100 degrees in the shade as crops withered in the fields and livestock were short on water all along Old State Road from the southern border of Madison County at Big Hill to the county seat in Richmond.”[xi].

The battle showcased the strength of the Confederate cavalry and opened a pathway north for the Confederate invasion of Kentucky. John Hunt Morgan and his Raiders envisioned this newly opened path as their gateway to greater glory and acclaim.

ENDNOTES

[i] Thomas, Edison H. "John Hunt Morgan and his Raiders,” Chap. 1 and 2, 2-3, 19-20.

[ii] Fletcher, Stephen Keyes. "The Civil War Journal of Stephen Keyes Fletcher," ed. Perry McCandless, Indiana Magazine of History 54, no. 2 ,June 1958, p.161.

[iii] Ramage, James A., “Rebel Raider” chap. 8, p.86

[iv] Swiggett, Howard, Bobbs, Merrill. “Raider and Terrible Men” Time, August 20, 1934.

[v] Bush, Bryan S. “The Civil War Battles of the Western Theatre” 1998, p. 37.

[vi] Ramage, James A. “Rebel Raider” chap. 11, p. 119.

[vii] Pucci, Kelly “Camp Douglas: Chicago’s Civil War Prison,” 2007 p.84.

[viii] Vandiver, Frank E. “Rebel Brass,” 1956.

[ix] Johnson, Ella. “Grandma Remembers,” 1928.

[x] CWSAC Battle Summaries: Richmond, http://www.nps.gov/history/hps/abpp/battles/ky007.htm

[xi] The Battle of Richmond Association. “A Brief History of the Battle: A great Confederate victory” http://www.battleofrichmond.org/HistoryBattle.htm

Beriah Magoffin

Monday, October 27, 2008

Slavery in Kentucky

"THE Legislature of Kentucky, by a very large majority, has pronounced in favor of the disfranchisement of any citizen of that State who advocates the emancipation of the negroes. The majority was not large enough—two-thirds—to give to the expression of opinion the force of law. But in a moral and philosophical point of view it was enough. A generation since, Kentucky came within two or three votes of being a free State. Now, to propose such a thing involves ostracism. Such has been the effect of cotton culture, and of the rapid increase of the negro population.

We should like to have a fresh vote on this question taken in a Legislature newly elected by the people of Kentucky. When the present Legislature was chosen, the rebels were contending for the mastery of the State. Possibly the subsequent progress of the Union army may have effected a change in public sentiment; though, we confess, we hardly dare think so.

This vote of the Kentucky Legislature seems the most discouraging event of the day."

~Harper's Weekly, April 12, 1862

Sunday, October 26, 2008

A Letter Home

Absolom Harrison, a Union solider with Company D, 4th Regiment, Kentucky Calvary Volunteers, was on duty in Bardstown, Kentucky, not far from the Evans’ home on the Caney Fork of Cox’s Creek, when he wrote to his wife.

“Bardstown, Ky

March 11th, 1862

Dear Wife,

I take my pen in hand to inform you that I am well at present and hope these few lines may find you all well. The boys from Hardin are all well. We are in Bardstown at present. Our company and ---- are acting as provost guards. We moved in here last Thursday. I expect we will stay here for some time. We are camped in a vacant lot in town. We have to stand guard here every other night. We are all so glad to get out of the mud and to get here on the dry street even if we were to stand guard every night. The talk about disbanding has nearly died away. I don't think there is any prospect of being disbanded. Yet I would be very glad if they would turn us loose and let us all go home. Jo rec'd Eliza's letter last night and we were glad to hear that you all was well. We have not got any money yet. They keep telling us we will get our money in a day or two so I don't know when we will get it. But I hope it won’t be many days more before we will be paid off. I don't know when any of us will be at home. The Captain has not let any of the men go home since I came back. Although he has promised Jo that he might go home as soon as we were paid off. We have one very unpleasant duty to perform here and that is burying the soldiers that die in the hospitals. There is about six hundred in the hospitals at this place and they die at the rate of about four per day. We also have to put out patrols of 5 or 6 men to walk around town and arrest every soldier without a pass or drunken men and put them in jail till they get sober. Tell father he may go on and sow them oats if he can get the seed for I will not be back in time enough to sow them no how. And if you can sell any of that corn for a good price you had better sell some of it and manage things the best you can until I can get back. You must write as often as you can. I looked hard for a letter yesterday but was disappointed when the mail came in and nearly all boys got letters but me. The war news from everywhere is cheering. The federal troops are gaining ground everywhere but it may be some time before peace is made. I must bring my letter to a close for it is nearly time to go on guard. So nothing more at present but remaining your affectionate husband until death.

A. A. Harrison

P.S. Kiss the children for me.”[i]

Interesting Aside: Susan Allstun Harrison, Absolom A. Harrison's wife was the granddaughter of Nancy Lincoln Brumfield. Nancy Lincoln Brumfield was the sister of Thomas Lincoln and aunt of President Abraham Lincoln.

ENDNOTES

[i] Letters of Absolom A. Harrison http://www.civilwarhome.com/letter4.htm

Saturday, October 25, 2008

A Minister’s Account of a “Colored Refugee Camp”

“I returned to Rochester in 1856, and took charge of the colored church in this city. In 1862 I received an appointment from the American Missionary Society to labor among the colored people of Tennessee and Louisiana, but I never reached either of these states. I left Rochester with my daughter, and reported at St. Louis, where I received orders to proceed to Louisville, Kentucky. On the train, between St. Louis and Louisville, a party of forty Missouri ruffians entered the car at an intermediate station, and threatened to throw me and my daughter off the train. They robbed me of my watch. The conductor undertook to protect us, but, finding it out of his power, brought a number of Government officers and passengers from the next car to our assistance. At Louisville the government took me out of the hands of the Missionary Society to take charge of freed and refugee blacks, to visit the prisons of that commonwealth, and to set free all colored persons found confined without charge of crime. I served first under the orders of General Burbage, and then under those of his successor, General Palmer. The homeless colored people, for whom I was to care, were gathered in a camp covering ten acres of ground on the outskirts of the city. They were housed in light buildings, and supplied with rations from the commissary stores. Nearly all the persons in the camp were women and children, for the colored men were sworn into the United States service as soldiers as fast as they came in. My first duty, after arranging the affairs of the camp, was to visit the slave pens, of which there were five in the city. The largest, known as Garrison's, was located on Market Street, and to that I made my first visit. When I entered it, and was about to make a thorough inspection of it, Garrison stopped me with the insolent remark, "I guess no nigger will go over me in this pen." I showed him my orders, whereupon he asked time to consult the mayor. He started for the entrance, but was stopped by the guard I had stationed there. I told him he would not leave the pen until I had gone through every part of it. "So," said I, "throw open your doors, or I will put you under arrest." I found hidden away in that pen 260 colored persons, part of them in irons. I took them all to my camp, and they were free. I next called at Otterman's pen on Second Street, from which also I took a large number of slaves. A third large pen was named Clark's, and there were two smaller ones besides. I liberated the slaves in all of them. One morning it was reported to me that a slave trader had nine colored men locked in a room in the National hotel. A waiter from the hotel brought the information at daybreak. I took a squad of soldiers with me to the place, and demanded the surrender of the blacks. The clerk said there were none in the house. Their owners had gone off with "the boys" at daybreak. I answered that I could take no man's word in such a case, but must see for myself. When I was about to begin the search, a colored man secretly gave me the number of the room the men were in. The room was locked, and the porter refused to give up the keys. A threat to place him under arrest brought him to reason, and I found the colored men inside, as I had anticipated. One of them, an old man, who sat with his face between his hands, said as I entered: "So'thin' tole me last night that so'thin' was a goin' to happen to me." That very day I mustered the nine men into the service of the government, and that made them free men.

So much anger was excited by these proceedings, that the mayor and common council of Louisville visited General Burbage at his headquarters, and warned him that if I was not sent away within forty-eight hours my life would pay the forfeit. The General sternly answered them: ‘If James is killed, I will hold responsible for the act every man who fills an office under your city government. I will hang them all higher than Haman was hung, and I have 15,000 troops behind me to carry out the order. Your only salvation lies in protecting this colored man's life.’ During my first year and a half at Louisville, a guard was stationed at the door of my room every night, as a necessary precaution in view of the threats of violence of which I was the object. One night I received a suggestive hint of the treatment the rebel sympathizers had in store for me should I chance to fall into their hands. A party of them approached the house where I was lodged protected by a guard. The soldiers, who were new recruits, ran off in affright. I found escape by the street cut off, and as I ran for the rear alley I discovered that avenue also guarded by a squad of my enemies. As a last resort I jumped a side fence, and stole along until out of sight and hearing of the enemy. Making my way to the house of a colored man named White, I exchanged my uniform for an old suit of his, and then, sallying forth, mingled with the rebel party, to learn, if possible, the nature of their intentions. Not finding me, and not having noticed my escape, they concluded that they must have been misinformed as to my lodging place for that night. Leaving the locality they proceeded to the house of another friend of mine, named Bridle, whose home was on Tenth Street. After vainly searching every room in Bridle's house, they dispersed with the threat that if they got me I should hang to the nearest lamp-post. For a long time after I was placed in charge of the camp, I was forced to forbid the display of lights in any of the buildings at night, for fear of drawing the fire of rebel bushwhackers. All the fugitives in the camp made their beds on the floor, to escape danger from rifle balls fired through the thin siding of the frame structures.

I established a Sunday and a day school in my camp and held religious services twice a week as well as on Sundays. I was ordered by General Palmer to marry every colored woman that came into camp to a soldier unless she objected to such a proceeding. The ceremony was a mere form to secure the freedom of the female colored refugees; for Congress had passed a law giving freedom to the wives and children of all colored soldiers and sailors in the service of the government. The emancipation proclamation, applying as it did only to states in rebellion, failed to meet the case of slaves in Kentucky, and we were obliged to resort to this ruse to escape the necessity of giving up to their masters many of the runaway slave women and children who flocked to our camp.

I had a contest of this kind with a slave trader known as Bill Hurd. He demanded the surrender of a colored woman in my camp who claimed her freedom on the plea that her husband had enlisted in the federal army. She wished to go to Cincinnati, and General Palmer, giving me a railway pass for her, cautioned me to see her on board the cars for the North before I left her. At the levee I saw Hurd and a policeman, and suspecting that they intended a rescue, I left the girl with the guard at the river and returned to the general for a detail of one or more men. During my absence Hurd claimed the woman from the guard and the latter brought all the parties to the provost marshal's headquarters, although I had directed him to report to General Palmer with the woman in case of trouble; for I feared that the provost marshal's sympathies were on the slave owner's side. I met Hurd, the policeman and the woman at the corner of Sixth and Green streets and halted them. Hurd said the provost marshal had decided that she was his property. I answered -- what I had just learned that the provost marshal was not at his headquarters and that his subordinate had no authority to decide such a case. I said further that I had orders to take the party before General Palmer and proposed to do it. They saw it was not prudent to resist, as I had a guard to enforce the order. When the parties were heard before the general, Hurd said the girl had obtained her freedom and a pass by false pretenses. She was his property; he had paid $500 for her; she was single when he bought her and she had not married since. Therefore she could claim no rights under the law giving freedom to the wives of colored soldiers. The general answered that the charge of false pretenses was a criminal one and the woman would be held for trial upon it. ‘But,’ said Hurd, ‘she is my property and I want her.’ ‘No,’ answered the general, ‘we keep our own prisoners.’ The general said to me privately, after Hurd was gone: ‘The woman has a husband in our service and I know it; but never mind that. We'll beat these rebels at their own game.’ Hurd hung about headquarters two or three days until General Palmer said finally: ‘I have no time to try this case; take it before the provost marshal.’ The latter, who had been given the hint, delayed action for several days more, and then turned over the case to General Dodge. After another delay, which still further tortured the slave trader, General Dodge said to me one day: ‘James, bring Mary to my headquarters, supply her with rations, have a guard ready, and call Hurd as a witness.’ When the slave trader had made his statement to the same effect as before, General Dodge delivered judgment in the following words: ‘Hurd, you are an honest man. It is a clear case. All I have to do, Mary, is to sentence you to keep away from this department during the remainder of the present war. James, take her across the river and see her on board the cars.’ ‘But, general,’ whined Hurd, ‘that won't do. I shall lose her services if you send her north.’ ‘You have nothing to do with it; you are only a witness in this case,’ answered the general. I carried out the order strictly, to remain with Mary until the cars started; and under the protection of a file of guards, she was soon placed on the train en route for Cincinnati.

Among the slaves I rescued and brought to the refugee camp was a girl named Laura, who had been locked up by her mistress in a cellar and left to remain there two days and as many nights without food or drink. Two refugee slave women were seen by their master making toward my camp, and calling upon a policeman he had then seized and taken to the house of his brother-in-law on Washington street. When the facts were reported to me, I took a squad of guards to the house and rescued them. As I came out of the house with the slave women, their master asked me: ‘What are you going to do with them?’ I answered that they would probably take care of themselves. He protested that he had always used the runaway women well, and appealing to one of them, asked: ‘Have I not, Angelina?’ I directed the woman to answer the question, saying that she had as good a right to speak as he had, and that I would protect her in that right. She then said: ‘He tied my dress over my head Sunday and whipped me for refusing to carry victuals to the bushwhackers and guerrillas in the woods.’ I brought the women to camp, and soon afterwards sent them north to find homes. I sent one girl rescued by me under somewhat similar circumstances as far as this city to find a home with Colonel Klinck's family.

Up to that time in my career I had never received serious injury at any man's hands. I was several times reviled and hustled by mobs in my first tour of the district about the city of Rochester, and once when I was lecturing in New Hampshire a reckless, half-drunken fellow in the lobby fired a pistol at me, the ball shattering the plaster a few feet from my head. But, as I said, I had never received serious injury. Now, however, I received a blow, the effects of which I shall carry to my grave. General Palmer sent me to the shop of a blacksmith who was suspected of bushwhacking, with an order requiring the latter to report at headquarters. The rebel, who was a powerful man, raised a short iron bar as I entered and aimed a savage blow at my head. By an instinctive movement I saved my life, but the blow fell on my neck and shoulders, and I was for a long time afterwards disabled by the injury. My right hand remains partially paralyzed and almost wholly useless to this day.

Many a sad scene I witnessed at my camp of colored refugees in Louisville. There was the mother bereaved of her children, who had been sold and sent farther South lest they should escape in the general rush for the federal lines and freedom; children, orphaned in fact if not in name, for separation from parents among the colored people in those days left no hope of reunion this side the grave; wives forever parted from their husbands, and husbands who might never hope to catch again the brightening eye and the welcoming smile of the help-mates whose hearts God and nature had joined to theirs. Such recollections come fresh to me when with trembling voice I sing the old familiar song of anti-slavery days:

Oh deep was the anguish of the slave mother's heart

When called from her darling forever to part;

So grieved that lone mother, that broken-hearted mother

In sorrow and woe.

The child was borne off to a far-distant clime

While the mother was left in anguish to pine;

But reason departed, and she sank broken-hearted

In sorrow and woe.

I remained at Louisville a little over three years, staying for some months after the war closed in charge of the colored camp, the hospital, dispensary and government stores.[i]

ENDNOTES

[i] James,Thomas. “Wonderful Eventful Life of Rev. Thomas James, by Himself” 1887, pages 16 -21.

Dark and Bloody Ground

With both Union and Confederate troops occupying the Commonwealth, it was inevitable that battles and skirmishes would occur.

Kentucky lived up to its fabled reputation as “Dark and Bloody Ground.”

November 8, 1861

Floyd County in Eastern Kentucky saw the Battle of Ivy Mountain.

“While recruiting in southeast Kentucky, Rebels under Col. John S. Williams ran short of ammunition at Prestonsburg and fell back to Pikeville to replenish their supply. Brig. Gen. William Nelson sent out a detachment from near Louisa under Col. Joshua Sill while he started out from Prestonsburg with a larger force in an attempt to “turn or cut the Rebels off.” Williams prepared for evacuation, hoping for time to reach Virginia, and sent out a cavalry force to meet Nelson about eight miles from Pikeville. The Rebel cavalry escaped, and Nelson continued on his way. Williams then met Nelson at a point northeast of Pikeville between Ivy Mountain and Ivy Creek. Waiting by a narrow bend in the road, the Rebels surprised the Yankees by firing upon their constricted ranks. A fight ensued, but neither side gained the bulge. As the shooting ebbed, Williams’s men felled trees across the road and burned bridges to slow Nelson’s pursuing force. Night approached and rain began which, along with the obstructions, convinced Nelson’s men to go into camp. In the meantime, Williams retreated into Virginia, stopping in Abingdon on the 9th. Sill’s force arrived too late to be of use, but he did skirmish with the remnants of Williams’s retreating force before he occupied Pikeville on the 9th. This bedraggled Confederate force retreated back into Virginia for succor. The Union forces consolidated their power in eastern Kentucky mountains.”[i]

The moving tale of Private William Barker, who was killed during the battle, can be found at http://www.geocities.com/Heartland/9999/PrivateWilliamBarker.html

November 18, 1861

During a Sovereignty Convention in Russellville, Confederate leadership established the Provisional Government of Kentucky. George W. Johnson was elected the governor and Bowling Green, Kentucky was selected as the capital of “Confederate Kentucky.”

Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston’s army was encamped at Bowling Green as protection for Governor Johnson's provisional government.

The Provisional Government was never able to replace the elected government in Frankfort, headed by Governor Beriah Magoffin. Magoffin refused to recognize Confederate attempt to establish a government within the Commonwealth. Much of the citizenry followed their Governor’s example.

December 10, 1861

Heedless to realities within the Commonwealth, the Confederate Congress in Richmond, Virginia recognized the Provisional Government and admitted Kentucky into the Confederate States of America. Kentucky was represented by the central star on the Confederate battle flag.

As the official elected Kentucky General Assembly had strong Union ties, Kentucky never succeeded from the Union. Kentucky offically remained a state of the Union.

Thus Kentucky became a Belle claimed by rival suitors and was doomed to have her heart destroyed.

December 28, 1861

The largest cavalry battle to take place in Kentucky during the Civil War was the Battle of Sacramento. Fought between the forces of Confederate Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest and Union Brigadier General Thomas L. Crittenden, this battle is sometimes referred to as “Forrest’s First Fight.”

Crittenden was charged with holding a line along the Green River. Forrest’s task was to break it. The fight, which began south of Sacramento, became a running battle through the town and continued for another two miles. In achieving victory, Forrest proved the strength and value of the Confederate cavalry.

Meanwhile, Northern banks in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia were facing a shortage of gold. Republican Congressman Elbridge C. Spaulding of New York, a member of the House Ways and Means Committee, proposed a solution. He drafted a bill suggesting that paper money, payable on demand by the U.S. Treasury but unbacked by gold or silver, be made the legal tender for all debts. The constitutionality of this idea was questionable, but Attorney General Edward Bates upheld its legality. His ruling sparked heated congressional debates.[ii]

Across the pond, neutral Englishmen were not above chiming in on the causes of the war:

"So the case stands, and under all the passion of the parties and the cries of battle lie the two chief moving causes of the struggle. Union means so many millions a year lost to the South; secession means the loss of the same millions to the North. The love of money is the root of this, as of many other evils. The quarrel between the North and South is, as it stands, solely a fiscal quarrel."

~ Charles Dickens, December 28, 1861[iii]

January 10, 1862

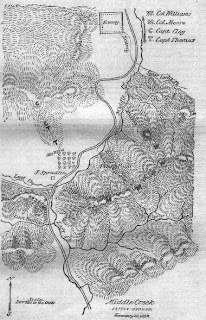

Kentuckian slew Kentuckian in hand-to-hand combat as the Battle of Middle Creek raged between forces under Union Colonel James A. Garfield and Confederate General Humphrey Marshall.

While a relatively same battle by Civil War standards, the battle was none the less poignant as the Confederate 5th Kentucky Infantry and Union 14th Kentucky Infantry faced each other in a literal “neighbor versus neighbor” battle.

With this decisive battle, Union forces halted the Confederate offensive in eastern Kentucky. The strategic advantage lost by the Confederates was never to be regained. The Confederates had lost control of Kentucky.

The results of the battle forever changed the lives of the two commanders. Former Ohio State Senator James Garfield gained national recognition after victory at Middle Creek. Returning to his political career at the war’s end, Garfield eventually became the 20th United States President. Humphrey Marshall a native of Kentuckywho had found fame as a hero of the Mexican War, had served as a four term U. S. Senator prior to the Civil War. Now blamed for defeat, Marshall spent the remainder of his military career under a shadow of doubt as Confederate authorities openly questioned his ability to lead.

January 19, 1862

The Battle of Mill Springs was fought in Pulaski County, Kentucky under Union General George H. Thomas and Confederate General George B. Crittenden.

During a nasty rain storm, Thomas launched an advance on Crittenden’s postion. Due to the heavy rains, the advance was so slow that Crittenden men were able to intercept them. It looked as if the Confederates would have an easy victory.

Yet, in the rain and darkness, Felix Zollicoffer,commander of Crittenden’s First Brigade, became disoriented. In an attempt to prevent tragedy, Lt. H. M. R. Fogg, charged in calling out to Zollicoffer. Alert Union soldiers took aim. Both Fogg and Zollicoffer were killed.

Union forces arrived from Somerset to reinforce Thomas and the Confederates were forced to retreat across the Cumberland River.

"I have been in the U.S. service for 4 months and have been marching ever since and was in the battle of Mills Springs and hoped to whip that old devil Zolly Coffer. I saw him when he fell in the field of battle. George, I tell you there was no fun in fighting. To hear the balls whistling over your head and cutting your clothes off and seeing men fall like hay before a scythe, it will scare a fellow a little. Battle is no chance for dodging. All we have to do is put our trust in God and keep our powder dry."

~ Private John H. Burch

“The battle of Mill Springs, along with one at Middle Creek broke whatever Confederate strength there was in eastern Kentucky.”[iv]

February, 1862

Confederate General Johnston retreated from Bowling Green moving his army southward into Tennessee.

Provisional Governor Johnson and his council, finding their government unprotected, were forced to flee into Tennessee. The Provisional Government was forced to set up its headquarters in army tents and travel with Kentucky Units of the Confederate Army.

“I am determined to share the dangers of the battle with these boys.”

~Governor George W. Johnson

During the battle at Shiloh, Governor Johnson insisted he be sworn in as a private. He flatly refused to stand idly by as Confederate boys fell. Taking up position despite his crippled arm, he fought along side the boys of Company E, 4th Kentucky Infantry until he was wounded in the right thigh and lower abdomen. Governor Johnson died aboard the Union hospital shipl Hannibal after having been mortally injured at Shiloh.

Most of Kentucky was now under Union military and political control but all was not going well in the North.

Abraham Lincoln, unable to stem the gold crisis, signed the Legal Tender Act into law. "Greenbacks" began to circulate early in April.[v]

ENDNOTES

[i] CWSAC Battle Summaries: Ivy Mountain http://www.nps.gov/hps/abpp/battles/ky003.htm

[ii] Faust, Patricia L "Historical Times Encyclopedia of the Civil War."

[iii] Dickens, Charles. "All The Year Round."

[iv] Bush, Bryan S. “The Civil War Battles of the Western Theatre ” 1998, p. 20.

[v] Faust, Patricia L. "Historical Times Encyclopedia of the Civil War."

Thursday, October 23, 2008

The Battle of Saratoga Springs, Kentucky

Union forces under Major Jesse J. Phillips made an early morning attack against roughly 160 men in a Confederate Training Camp at Saratoga Springs in Lyon County, Kentucky. The attack resulted in another Union victory.

“Our skirmishers succeeded in surrounding and capturing the rebel pickets without firing a gun, and the advance of our troops was unsuspected by the rebels until we wheeled in column of platoon in the lane of full view, 600 yards distant from their camp at about 7 A.M. They, to the number of about 160 men, dismounted immediately formed in line, awaiting our attack until we advanced within 22 years of their line. We, when first coming in sight, having charged on them the double quick, they commenced an irregular fire when we were a distance of 300 yards, but at our approach broke for their horses, though many took shelter behind fences, trees or houses. We charged within 50 yards, halted, delivered a volley, and then charged bayonet, driving them from the houses and from their places of cover, and they then fled in every direction, some on foot, others on horseback. An occasional firing was kept up for half an hour or more. Six of their men were left dead and one mortally wounded. Several others were seen to ride off clinging to their horses and were wounded.”

~ Report of Major Jesse J. Phillips

According to Lyon County historian, Odell Walker, the bullet holes in the original siding of the Saratoga United Methodist Church bear proof to the location of the battle. Mr. Walker, a most generous gentleman, graciously granted permission to reproduce the following article in full:

The Battle of Saratoga

“In 1798, David Walker, the founder of Eddyville, appeared before the Christian County Court and made a request that a road be laid out from the Eddy Cabbins on the Cumberland River to Prince’s Place at the Big Spring.

The Eddy Cabbins was a campsite for river travelers at the mouth of Eddy Creek, and Prince’s Plcase was the home of William Prince, which later became Princeton.

Walker’s request was granted and the road followed the general corridor of present day Highway 293. The road was later referred to as the Princeton-Eddyville Turnpike. Before the impoundment of Lake Barklery, U.S. Highway 62 followed the same route to Old Eddyville and on to Old Kuttawa.

Approximately four miles east of the old town of Eddyville, on the above named road, was a large spring that flowed into Glass Creek.

When Matthew Lyon and his party arrived at Eddyville in 1802, Lyon’s stepson, Elisha Galusha, was assigned the land around this spring, and for many years, it was called Galusha Spring.

Because of the road, Galusha Springs became a favorite stopping place for travelers to get a drink of fresh water and water for their horses. Because of the level ground and plenty of shade, the Spring became a favorite place for picnics and other gatherings.

In 1822, the pioneer Methodist preacher, Benjamin Ogden, deeded a parcel of land to Reed’s Chapel or Reed’s Campground, upon which a log meeting house was erected.

By the 1850’s, a community had developed in the area consisting of a country store, post office and tavern.

According to legend, a group of young men and boys were looking for mischief one Halloween night. They had heard or read of Saratoga Springs, N.Y. They took a long plan and painted “Saratoga Springs” on it and nailed it over the door of the store. They thought this would make the store owner angry, but much to their surprise, when the owner arrived the next morning to open up, he liked the new name, and thus, the community became known as Saratoga Springs.

The name Reed’s Chapel was changed to Saratoga Methodist Church, and in 1859 a new frame church edifice replaced the original log building.

On Oct 15, 1861, a troop of Calvary was mustered into Confederate service at Hopkinsville. The unit became Company “G”, First Kentucky Calvary, and a majority of the members were from Lyon and Caldwell County.

Company “G” was placed under the command of Captain M.D. Wilcox and assigned for training at Saratoga Springs. The group had a double responsibility; first, they were engaged in military training; second, they were to serve as rangers or scouts to watch for the movement of federal troops overland. The area to be patrolled was from Cave-In-Rock, on the Ohio River, to Hopkinsville.

Saratoga Springs was an ideal location for a small group training camp with an abundance of water, both spring and creek, level land for military drills and nearby foothills for firewood.

The camp at Saratoga Springs was destined to be short-lived. On Sept 6, 1861, General U.S. Grant captured and took possession of Paducah. Brigadier General C. F. Smith was in command of the Union forces at Paducah and received intelligence of Captain Wilcox’s activities at Saratoga Springs.

On Oct 25, 1861, three full companies of infantry consisting of 300 men were dispatched to Saratoga Springs. This group was under the command of Major Jesse J Phillips. At 4:30 p.m. the troops staged a parade for General Smith and were issued two days of rations. The troops boarded the steamer, “Lake Erie” and pulled away from the Paducah wharf, under the escort of the gunboat, “Conestoga.”

The boats steamed up the Ohio River to Smithland and turned into the Cumberland River. They continued upstream to a pre-selected landing at William Kelly’s New Union Forge. This site later became the town of Kuttawa.

Under the cover of darkness, the troops disembarked and marched northward to the area of the old Kuttawa Springs and continued north along Hammond Creek for a distance of about five miles. From this point, the troops traveled in a northeast semi-circle to the Eddyville-Princeton road to a point about a mile east of Saratoga Springs.

The success of the Saratoga raid depended on total surprise and this was accomplished by avoiding established roads and traveling through fields and woods. The Confederates at Saratoga Springs misjudged the plan of the Union Army. The Confederates anticipated that should an attack occur, the enemy would travel north on the Varmint Trace Road and turn east on the Liberty Church Road to Saratoga Springs. A watchman was stationed at Liberty Church, but this point was passed by the Union Soldiers.

The Union forces arrived on the Eddyville-Princeton road at about daybreak on the morning of the 26th, and at approximately 7 A.M. they went into formation to attack the Confederate Camp at Saratoga Springs.

The following is taken from Major Phillip’s official report of the battle: “Our skirmishers succeeded in surrounding and capturing the rebel pickets without firing a gun, and the advance of our troops was unsuspected by the rebels until we wheeled in column of platoon in the lane of full view, 600 yards distant from their camp at about 7 A.M.

They, to the number of about 160 men, dismounted immediately formed in line, awaiting our attack until we advanced within 22 years of their line. We, when first coming in sight, having charged on them the double quick, they commenced an irregular fire when we were a distance of 300 yards, but at our approach broke for their horses, though many took shelter behind fences, trees or houses.

We charged within 50 yards, halted, delivered a volley, and then charged bayonet, driving them from the houses and from their places of cover, and they then fled in every direction, some on foot, others on horseback. An occasional firing was kept up for half an hour or more. Six of their men were left dead and one mortally wounded. Several others were seen to ride off clinging to their horses and were wounded.”

The Saratoga Methodist Church building still has bullet holes to attest to the battle.

The newly enlisted and untrained Confederate soldiers were no match for a well-trained and seasoned Union Army.

In the meantime, the steamers, Lake Erie and Conestoga, had moved up to Eddyville and docked, awaiting the arrival of the troops for the trip back to Paducah.

The Union Army took ConfederatecContraband including 30 horses, several mules, 40 saddles, 30 bridles, harness, two wagons, 30 blankets, several rifles, shotguns, sabers, swords, etc.

The Union Army, with their contraband and several Confederate prisoners, marched on down the Eddyville-Princeton road from Saratoga Springs to Eddyville, boarded the waiting boats for the return trip to Paducah.”

~ Odell Walker[i]

ENDNOTES

[i] “Our Heritage: A Look Back At The History of Lyon County,” The Lyon County Historical Society and The Herald Ledger Newspaper, July 3, 1996. Mr. Walker is also the author of, “Profiles of the Past” 1994 , which offers in depth information regarding the battle.

Them Cotton Fields Back Home

Cartoon published in Punch on November 2, 1861. The restraint across the king’s stomach reads, “ BLOCKADE”

Cartoon published in Punch on November 2, 1861. The restraint across the king’s stomach reads, “ BLOCKADE”In 1858 Senator James Henry Hammond of South Carolina declared,

"Without the firing of a gun, without drawing a sword, should they make war upon us, we could bring the whole world to our feet. What would happen if no cotton was furnished for three years? England would topple headlong and carry the whole civilized world with her. No, you dare not make war on cotton! No power on earth dares make war upon it. Cotton is King."

His words would prove prophetic as during the Civil War, cotton dominated international relations.

On May 13, 1861, Queen Victoria issued a proclamation of neutrality which recognized the Confederacy as “having belligerent rights.”

By the Autumn of 1861, Europeans, particularly the English, began to take note of American Civil War due to the blockade of Southern ports. The blockade, imposed as part of the Anaconda Plan, had cut off all legitimate imports and hit British business men squarely in the pocketbook. The Confederates had been importing every imaginable war material from cannons and guns to footwear, uniforms, and hospital supplies.

“The contest is really for empire on the side of the North and for independence on that of the South...”

~ London Times 7 November 1861

Such notice was exactly what the South had been anticipating.

The London Times took a pro-Confederacy stance as did many of the Crown subjects. As numerous Southerners maintained active family, social, and business relations with Englishmen, it was not surprising that Southern military leaders such as Lee and Jackson were well respected in England. In addition, the concept of the South breaking free from Northern tyranny was well received. Thus, Confederate Leadership predicted that the British Navy would break the blockade or at least escort ships through it and into Southern port.

Reality was not to be all the Confederates had envisioned. The British Navy remained neutral and did not interfere with the blockade. This however, did not prevent many private ships of British registry from becoming blockade runners. These ships stealthily voyaged to and from Nassau, Bermuda, and Havana to bring supplies to the beleaguered Confederates.

On November 8, 1861, the United States Government found itself in a predicament with Great Britian. The Confederacy hoped to make the most of this diplomatic fiasco. The U.S. Naval ship San Jacinto forced the British ship Trent, which carried two Confederate commissioners, to stop in international waters. The Trent was then boarded and the two Confederates, James M. Mason, commissioner to London and John Slidell, commissioner to Paris, were taken prisoner. This action was a violation of maritime law. War between England and the United States was narrowly averted when U. S. Secretary of State William Seward apologized. Orders were given to release of the commissioners from their imprisonment in Fort Warren on January 1, 1862.

The Confederate Leadership still firmly believed “Cotton is King.” They were dead sure that Great Britian and France would come to their aid as allies in order to obtain Southern cotton. The Confederacy hoped to sway England and France through an embargo of cotton. Although the Confederate Congress never formally established the embargo, local "committees of public safety" prevented cotton exports. Thus, the cotton crop was horded into great warehouses, awaiting pledges of allegiance. Much to Confederate distress, help never came. The horded crop began to rot.

England simply purchased cotton from Indian and the Caribbean. The French procured cotton from Egypt. Europeans simply did not view Southern cotton as a worthy cause for engaging in war.

The South was left to stand alone.

Sunday, October 19, 2008

A Pocket Full of Wry

Cartoon published in Harper’s Weekly on September 21, 1861 and captioned “KING COTTON. Oh! Isn’t that a Dainty Dish to set before the King?"

Cartoon published in Harper’s Weekly on September 21, 1861 and captioned “KING COTTON. Oh! Isn’t that a Dainty Dish to set before the King?"From this drawing, it would seem the North still harbored ill feelings toward England and cared little if the blockade of Southern ports prevented the English from obtaining cotton.

Saturday, October 18, 2008

The Hercules of 1861

"In this political cartoon, a Union officer (unidentified) swings a club labeled "Union" in defense against a many-headed serpent labeled "Secession." The serpent's heads are: Floyd, Pickens, Beauregard, Twiggs, Davis, Stephens, and Toombs, all leaders of the Southern secession movement and the resulting Confederacy. "

~ Courtesy of Civil War Treasures, New York Historical Society

The Strains of Music

I am haunted.

It is neither the fact that a “lady” of the period would feel forced to publish anonymously nor the stilted, flowery language of the song that leave my mind so troubled.

I am disturbed by the eagerness to die, the enthusiasm to send husbands and sons into battle, the vision of a war sanctioned by God.

Please note this work has been published as found, no corrections have been made.

"The Southron's Chaunt of Defiance" (1861)

Words by a Lady of Kentucky

Music by Armand Edwand Blackmar

You can never win us back;

Never! Never!

Tho' we perish in the track

Of your endeavor;

Tho' our corpses strew the earth

Smiling now on our birth,

And tho' blood polute each hearth

Now and ever!

We have risen to a man,

Stern and fearless;

Of your curses, of your ban,

We are careless.

Ev'ry hand is on its knife,

Ev'ry gun is primed for strife.

Ev'ry palm contains a Life

High and peerless.

You have no such blood as our

For the shedding;

In the veins of Cavaliers

Was its heading!

You have no such stately men

In you abolution den

Marching through foe and fen,

Nothing dreading!

We may fall before the fire

Of your legions,

Paid with gold for murderous hire,

Bought allegiance;

But for every drop you shed,

You shall have a mound of dead,

So that vultures may be fed

In our regions!

But the battle to the strong

Is not given,

While the Judge of right and wrong

Sits in Heaven

And the God of David still

Guides the pebble in His will,

There are giants yet to kill,

Wrongs unshriven!

What Have We Gotten Ourselves Into?

Few men, Northern or Southern, realized the gravity of the war they had entered.

“Everyone in Washington believed that the war would end quickly. The North claimed the loyalty of twenty-three states with a population of 22 million. The eleven states of the Confederacy had about 9 million people and nearly 4 million of them were slaves. The South was mainly agricultural. The North had factories to produce ammunition and guns, a network of railroads to transport troops, and a powerful navy that could blockade Southern ports.

But if the North had most of the industry and population, the South held a monopoly on military talent. Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president, was a professional soldier. And Southerners made a high proportion of the country’s skilled military commanders. Lincoln’s biggest headache during the early years of the war would be to find competent generals who could lead the union to victory.” [i]

October 8, 1861

Lincoln rued his lack of capable officers. Thus, after critical refection on the best use of the leaders he had, strategical changes were made. U. S. Brigadier General Don Carlos Buell replaced General William T. Sherman as commander of the Department of the Cumberland, responsible for the Federal military in Kentucky.

"The object is not to fight great battles, and storm impregnable fortifications, but by demonstrations and maneuvering to prevent the enemy from concentrating his scattered forces... [T]he commander merits condemnation who, from ambition or ignorance or a weak submission to the dictation of popular clamor and without necessity or profit, has squandered the lives of his soldiers."

~ Brigadier General Don Carlos Buell

October 14, 1861

General Sherman took over responsibility for Federal military preparations and operations in Kentucky from Gen. Robert Anderson.

Poor Lincoln, doomed to be vexed with military leadership throughout the war, reached the point of exasperation. In desperation, he resolved to take matters into his own hands. Lincoln made himself into a true Commander-in-Chief.

“By now, the president had serious misgivings about the professional soldiers who were running the war. He had collected a library of books on military strategy, and he studied them late into the night, just as he had once studied law and surveying. Attorney General Edward Bates had told Lincoln that it was his presidential duty to ‘command the commanders….The nation requires it, and history will hold you responsible.’ Lincoln began to play an active role in the day-today conduct of the war, planning strategy and sometimes directing tactical maneuvers in the field.”[ii]

Resourcefulness was also needed when searching for the capitol needed to finance the war.

“Largely thanks to Cooke [Jay Cooke], The North was able to throw much of the cost of the war onto the future, raising two-thirds of its revenues in the war years by selling bonds. The Confederacy, with a far smaller middle class, few large banks, and little financial expertise, was able to raise only about 40 percent of its revenues through borrowing. The situation for the South was made worse by the fact that the South had an economy notoriously lacking in liquidity. Thus the South’s wealth could not be easily translated into money and spent on war materiel. While the South had 30 percent of the country’s total assets at the outbreak of the war, it had only about 12 percent of the circulating currency and 21 percent of the banking assets. The word land-poor was not invented until Reconstruction days, but it also described the Southern economy in 1861.” [iii]

October 21, 1861

The Confederacy wasn’t always doing so well on the battle field either.

The Battle of Camp Wildcat, fought in Laurel County, Kentucky was one of the earliest engagements of the Civil War. Confederate forces under the leadership of Brig. Gen. Felix Zollicoffer moved up from Tennessee through the Cumberland Gap. They were repelled by Union troops under the command of Col. Theophilous T. Garrard and reinforcements under the command of Brig. Gen. Albin F. Schoepf. The battle resulted in Union victory.

Yet, nothing dimmed the resolved of “Johnny Reb.” The men who had become Confederate soldiers believed themselves to be fighting for the right of their people to govern themselves and fend off a foreign invasion of their sovereign soil.

"The rank and file were chiefly farmers and small merchants, comparatively very few were owners of slaves; but they were all descended from ancestors whose fortunes and blood had been freely spent in the war of the revolution; they volunteered in obedience to the call of their state to resist invasion; they came with a firm determination to do their full duty."

~ Capt. Wm. H. S. Burgwyn, 35th Regiment, North Carolina Troops

"In the Civil War, the common soldiers of both sides were the same sort of people; untrained and untaught young men, mostly from the country. There weren't many cities then, and they weren't very large, so the average soldier generally came from either a farm or from some very small town or rural area. He had never been anywhere; he was completely unsophisticated. He joined up because he wanted to, because his patriotism had been aroused. The bands were playing, the recruiting officers were making speeches, so he got stirred up and enlisted. Sometimes, he was not altogether dry behind the ears." [iv]

Friday, October 17, 2008

Johnny Has Gone For a Soldier

“With fife and drum he marched away

He would not heed what I did say

He'll not come back for many a day

Johnny has gone for a soldier.” [ii]

During the first few days of the Civil War, Northern religious leaders, ever the lions of the pulpit, seized upon a critical moment indoctrinate their flocks.

“After Confederate forces opened fire on Fort Sumter in April 1861, the vast majority of Northern religious bodies—with the exception of the historic "peace" churches which on principle adhered to pacifism—ardently supported the war for the Union.” [iii]

April 15, 1861

“I will send not a man, nor a dollar, for the wicked purpose of subduing my sister Southern states.”

~ Governor Beriah Magoffin [iv]

The following week, Magoffin, true to his netrual stance, rejected a similar call for troops from Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Religious leaders were also forced to turned the focus of their attention to the war.

“Winter has gone and spring has come again, the gayest and loveliest of the seasons. How pleasant it is to walk forth in the green meadows or on the sunny side of the flower-decked hills! The orchard regales our senses with its fragrant blossoms, the groves and the meadows are clothing themselves in living green, the singing of birds has come, and all nature is joyous with new life. But alas, the din of war, and clash of arms are distracting our once happy land. The sectional strife, arising chiefly from the unfortunate contest about slavery, has culminated, and the result is a civil war between the north and the south. The attack of the secessionists on Fort Sumter has aroused such indignation in the loyal people of the free states that they are unanimous in favor of chastising the offenders. Active preparations for war are going on throughout the whole land. The President [Lincoln] has made a requisition upon the states for 75,000 men, and will soon call for more.”

~ Rev. Abraham Essick, Lutheran minister [v]

Ministers, such as Reverend Essick, became disseminators of propaganda during the war. The simple act of going to church became tantamount to attending a weekly war rally. Religious leaders felt duty bound to arouse patriotic frenzy within their congregations.

“It’s instructive to realize that most of those who attended local churches in the South during the war—and therefore listened week after week to their local pastor sacralizing the Southern war cause—were women and children. With husbands, sons and fathers off at war, women filled the pews, and in turn, the preachers filled the women’s hearts and minds with a new sense of their place in both politics and public action. It would be the women, they understood, who would be keeping the godly “covenant” with their morality, prayers, and home-front support of the war.”[vi]

May 28, 1861

Governor Magoffin, a Democrat, issued a proclamation formally declaring Kentucky's neutrality. Moderates hoped Kentucky could become a buffer zone between the North and South and act as a broker of peace. These hopes proved fruitless as both the Union and the Confederacy failed to pay heed.

The Confederate government was already trying to pull itself out of a calamitous predicament. Having been short sighted in regard to the financing of both a new nation and a large scale war; the Confederacy found itself in dire need of capitol. Thus it was forced to print unbacked currency.

“As early as May 1861 the Confederate government was issuing treasury notes that would not be redeemable in gold and silver until two years after the signing of a peace treaty establishing independence.” [vii]

September 3, 1861

Confederate forces, under General Leonidas Polk, marched into Kentucky and occupied the towns Columbus and Hickman. General Polk was resolved to occupy the rail terminal at Columbus, which a strong and defensible position along the Mississippi River. In the mid-1800’s rivers were important trade and transportation routes. Keeping the river transportation systems to remain open was imperative to the Confederacy. They had to have access to the river in order to export cotton, import war materials, and insure a means of rapid transportation. Kentucky statesmen wanted river traffic to remain open as well. Hemp and whiskey produced in Kentucky were shipped to Southern and European markets via the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. If the North could manage to interrupt river traffic, Kentucky's economy would suffer.

“In 1861, Polk accepted a commission as a major general in the Confederate Army. Though on leave from his duties as bishop, ‘the bishop-general’ was criticized in the North for serving jointly as churchman and warrior. Southerners saw it differently. ‘Like Gideon and David’ the Memphis Appeal proclaimed, ‘he is marshaling his legions to fight the battle of the Lord.’" [viii]

The North was well aware of how much the Confederacy dependent on the rivers. Thus, war wizened seventy-five-year-old General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, in developing the “Anaconda Plan,” called for taking control of the Mississippi River and blockading Southern ports to squeeze the import dependant Confederacy into submission.

"But what a cruel thing is war to separate and destroy families and friends, and mar the purest joys and happiness God has granted us in this world; to fill our hearts with hatred instead of love for our neighbors, and to devastate the fair face of this beautiful world."

~ General Robert E. Lee

September 5, 1861

Union forces under General Ulysses S. Grant moved to occupy Paducah, Kentucky to the north of Polk’s position.

Throughout the remainder of the war, the Confederate and Union Armies would seek control of the Commonwealth by means of invasion, occupation, and battle. Kentucky was strategically important to both the North and South. Both the North and South looked to Kentucky for supplies of tobacco, corn, wheat, hemp, and flax. However, it was the Confederacy that eyed Kentucky and the Ohio River as a both defensible boundary and a staging point for attacks against Northern targets.

South ministers proclaimed that the soldier was fighting for God. They further asserted that gentlemanliness and commitment to the Confederate Cause were Christian virtues.

“Religion, in other words, was not merely a rationalization, not merely ideology, but the very core of the Confederate nation. ..Indeed, it was the Confederacy and not its enemy who inscribed ‘Almighty God’ into its Constitution and who raised ‘God Will Avenge’ as its motto. Jefferson Davis frequently invoked the Christian God even as Abraham Lincoln spoke in more mystical religious language. The Confederacy considered itself the first great Christian nation, the instrument of God’s will, the beginning of something rather than its end.” [ix]

“When war broke out, [William] Pendleton[an Episcopal priest] reentered the military and quickly became the Confederate chief of artillery. In his first battle, Pendleton commanded four guns, which he dubbed ‘Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.’ He gave the command, ‘While we kill their bodies, may the Lord have mercy on their sinful souls—FIRE!’" [x]

September 11, 1861

Following the violation of Kentucky's neutrality, first by Confederate General Polk and then by Union General Grant, the pro Union Kentucky General Assembly passed a resolution calling on Governer Magoffin to order only the Confederate troops out of Kentucky. Magoffin vetoed the resolution but the General Assembly overrode his veto and Magoffin was forced to issue the proclamation. Citizens with Confederate sympathizes were outraged at the legislature's decision, arguing that Polk's troops had entered Kentucky only to counter Grant’s movements.

Meanwhile, all Southerners, including the Confederate troops, were feeling the effects of the blockade.

“Rations were light, provisions of all sorts scarce, luxuries unknown, and clothing without suspicion of style or fashion. Cut off by the blockade from foreign supplies, we were dependent upon home resources, already overtaxed and imperfect, for almost everything. Only cornbread, peas, and sorghum were plentiful. The latter took the place of molasses, and at the same time was known as ‘long sweetening,’ in the place of sugar, for our coffee, which consisted of parched rye or dried sweet potatoes. It was also the saccharine element of the ‘pies’…, they being the first investment from his meager pay. Only the blockade runners, or their intimate friends, could indulge in the luxuries of eating, and drinking, or in the display of fine clothes.”

~ John H. Claiborne, M. D. [xi]

September 18,1861

The Kentucky General Assembly officially abandoned the position of neutrality and declared for the Union. Union troops massed just across the state boarders with Ohio and Illinois strongly influenced this choice. Claims have been made that if the General Assembly had not declared for the Union, these troops would have crossed the river intent on conquering the Commonwealth.

"I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game."

~ Abraham Lincoln, September 1861

With the General Assembly taking a pro-Union position, men who had publicly taken stances as Confederate sympathizers no longer felt comfortable residing in the Commonwealth. Late in the evening of September 20, 1861, under the cover of darkness, John Hunt Morgan secreted weapons and members of his Lexington Rifles militia unit out of Kentucky. The following evening, Morgan and a group of about twenty men made their escape. All of these men joined the Confederate Army once they reached the safety of Tennessee.

“Ann Clay, wife of pro-Union Kentucky legislator Brutus Junius Clay, found her stepson's bed empty but for this note stating that he had gone to join the Confederate army:

September 24, 1861

B.J. Clay and family,

I leave for the army tonight. I do it for I believe I am doing right. I go of my own free will. If it turns out I do wrong I beg forgiveness.

Goodbye to you all. You will hear from me soon.

[i] The Library of Congress/American Memory ,Digital ID: g3701s cw0011000.

[ii] Kendrew of York, mid nineteenth century broadside, original lyrics and melody can be traced to Irish origins.

[iii] Moorhead, James Howell. “Religion in the Civil War: The northern Side,” National Humanities Center http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/nineteen/nkeyinfo/cwnorth.htm

[iv] Powell, robert A. “Kentucky Governors” 1976.

[v] Diary of Rev. Abraham Essick.

[vi] Stout, Harry S. and Edwards, Jonathan., “ Civil War: The Southern Perspective,” National Humanities Center http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/nineteen/nkeyinfo/cwsouth.htm

[vii] Gordon, John Steele. “An Empire of Wealth : The Epic history of American Economic Power” p. 195.

[viii] Scott, Jeffery Warren and Jeffreys, Mary Ann. “Fighter of Faith” http://www.christianitytoday.com/holidays/memorial/features/33h034.html

[ix] Ayers, Edward L. “Reviews” The Journal of Southern Religion, 1998-99.

[x] Scott, Jeffery Warren and Jeffreys, Mary Ann. “Fighter of Faith” http://www.christianitytoday.com/holidays/memorial/features/33h034.html

[xi] Mitchell, Patricia B. “ Confederate Camp Cooking” 1991.

[xii] Berry, Mary Clay. “Voices from the Century Before: The Odyssey of a 19th Century Kentucky Family” 1997.

Thursday, October 16, 2008

Shots Fired: The Attack on Fort Sumter

The presidential elections of 1860 polarized the nation. Southern statesmen, fearing the Southern economy would collapse if limitations on slavery were imposed by Northern Republicans, threatened to break from the Union if a Republican was elected president.

Far from being shaken by the threat, the leading Republican candidate had other concerns on his mind.

“Shortly before the election, Lincoln received a letter from Grace Bedell, an eleven-year-old girl in Westfield, New York, suggesting that he grow a beard. ‘… you would look a great deal better for your face is so thin,’ she wrote. ‘All the ladies like whiskers and they would tease their husbands to vote for you.’ As he waited for the nation to vote, Lincoln took her advice.”[i]

When Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860, the South felt its concerns were no longer being heard in Washington.. Abraham Lincoln, the very Republican Southerners had reviled since he delivered a speech at Cooper Union arguing the Federal government’s power to limit slavery in newly formed states, carried the electoral votes in the North. Southerners, firm believers in State’s rights, had argued that both the new states and the state already formed had the right to determine their own laws regarding slave ownership. Consequently, the South divided its votes between Kentucky native John C. Breckenridge, a Southern Democrat, and John Bell of Tennessee, a Constitutional Unionist.

Regardless of Southern disapproval, Abraham Lincoln was about to become the next United States president. He would inherit a beleaguered economy and a Union on the brink of dissolve.

“Because of the depression that had started in 1857, the federal government had been operating in deficit since that time. In 1860 the national debt stood at $64,844,000 and the Treasury was nearly depleted. In December of that year, as the Deep South states began to secede one by one, there was at one point not even enough money on hand to meet the payroll.” [ii]

December 20, 1860

“If the Union was formed by the accession of States, then the Union may be dissolved by the secession of States"

~ Daniel Webster, 1833

In disgust over the election, South Carolina seceded from the Union. Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas followed by February 1861. The Confederate States, believing themselves to be a new and sovereign nation, began the take over of forts from Federal soldiers. This task was accomplished without incident. Soon, only two forts staffed by Federal troops remained in Confederate territory. These forts, Fort Pickens in Florida and Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, were surrounded by Confederate troops and effectively blockaded.

"We affirm that these ends for which this Government was instituted have been defeated, and the Government itself has been made destructive of them by the action of the non-slaveholding States. Those States have assume the right of deciding upon the propriety of our domestic institutions; and have denied the rights of property established in fifteen of the States and recognized by the Constitution; they have denounced as sinful the institution of slavery; they have permitted open establishment among them of societies, whose avowed object is to disturb the peace and to eloign the property of the citizens of other States. They have encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves to leave their homes; and those who remain, have been incited by emissaries, books and pictures to servile insurrection."

~ The Declaration of Secession for South Carolina

“Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery - the greatest material interest of the world. Its labor supplies the product which constitutes by far the largest and most important portions of commerce of the earth."

~ The Declaration of Secession for Mississippi

"For the last ten years we have had numerous and serious causes of complaint against our non-slave-holding confederate States with reference to the subject of African slavery. They have endeavored to weaken our security, to disturb our domestic peace and tranquility, and persistently refused to comply with their express constitutional obligations to us in reference to that property, and by the use of their power in the Federal Government have striven to deprive us of an equal enjoyment of the common Territories of the Republic."

~ The Declaration of Secession for Georgia

Yet, while South Carolina, Mississippi, and Georgia defended slavery, Jefferson Davis maintained his stances that secession was simply a matter of state’s rights.

“[Our situation] illustrates the American idea that governments rest on the consent of the governed, and that it is the right of the people to alter or abolish them whenever they become destructive of the ends for which they were established.”

~ Jefferson Davis

Meanwhile, the average citizen found the reality of secession difficult to comprehend.

“…as late as Christmas-time of the year 1860, although the newspapers were full of secession talk and the matter was eagerly discussed at our tables, coming events had cast any positive shadow on our homes. The people in our neighborhood, of one opinion with their dear and honored friend, Colonel Robert E. Lee, of Arlington, were slow to accept the startling suggestion of disruption of the Union.”

~ C. C. Harrison[iii]

Believing that he could prevent war by creating a gun so powerful that mankind would be unwilling to unleash its horrific carnage, Dr. Richard Gatlin patented the Gatling Gun. His hand cranked, multi-barreled weapon was capable of firing 200 rounds per minute. While it did not prevent the Civil War, it did reduce the number of soldiers needed to hold a position.

“It occurred to me that if I could invent a machine - a gun - which could by its rapidity of fire, enable one man to do as much battle duty as a hundred, that it would, to a large extent supersede the necessity of large armies, and consequently, exposure to battle and disease [would] be greatly diminished.”

~ Dr. Richard Jordan Gatlin[iv]

February 9, 1861

Abraham Lincoln was yet to grasp the fact that a war was inevitable. He failed to comprehend that many political and religious leaders of the day had abandoned both reason and tolerance. Imperturbable temperaments had become scarce commodities.